Tony D. Weinbeck (University of Wyoming, Department of Physics and Astronomy), William H. Waller (Endicott College, School of Science and Technology, and The Galactic Inquirer).

Abstract

Due to its large angular size and modest inclination, the Sc(s) II-III galaxy M33 is well-situated for studying extragalactic star formation. We combine Spitzer IRAC and MIPS infrared data, as well as optical H-alpha imagery, to create a multi- wavelength mosaic of the multi-phase ISM in M33. Using these data, we then focus on 8 prominent HII regions, studying the interplay of the PAHs, dust, and ionized gas in these regions. Besides assessing the multi-wavelength images of these HII regions, we measure the radial distribution of each wavelength component from the central core outward in each region. These distributions show the 24μm-emitting dust to be the most compact component, and hence the best tracer of the clustered high-mass star formation. The HII regions NGC 604 and IC 133 show especially strong evidence for dust-embedded star formation. We also investigate the relative abundance of each interstellar phase as a function of galactocentric radius. The 8μm-emitting PAHs and 24μm-emitting dust are seen to fall off with radius faster than the H-alpha-emitting ionized gas. This behavior is likely due to an actual decrease in the abundance of PAHs and dust at large galactocentric radius.

Introduction

Messier 33, a nearby Sc(s) II-III type spiral galaxy, offers astronomers some of the best viewing of galaxy-wide star forming activity. As a member of the Local Group of galaxies, M33 is only 840 kpc away (Freedman et al. 2001). It has an inclination of 52 degrees (Corbelli & Salucci 2000) that is sufficiently low to enable well-resolved studies of its disk. These factors, combined with an abundance of HII regions, make M33 an excellent source for studying extragalactic star formation in a comprehensive manner. M33 also provides an important testbed for assessing the effects of metallicity variations on star-forming environments, as its average O/H and N/H abundances decline with respect to galactocentric radius by factors of 1.5 and 3.1, respectively (Rosolowsky and Simon 2008; Koning 2016).

As is well known, massive star formation occurs in nebulae known as HII regions. These are formed from giant molecular clouds which, due to instabilities in the clouds, begin to collapse and form massive UV-emitting stars. The radiation from these stars ionizes the nearby hydrogen gas, producing regions of singly-ionized hydrogen known as HII regions. These HII regions can be giant – up to hundreds of light years across – and are most readily detected by the crimson H-alpha emission line at 656.3 nm wavelength (Shields 1990).

In addition to ionized hydrogen, there are also substantial amounts of dust and organic molecules present in HII regions. In particular, spectroscopic studies at infrared wavelengths have shown the presence of organic molecules known as Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (or PAHs). These carbon and hydrogen-rich molecules consist of sheet-like arrangements of benzene rings C6H6, whose bending and stretching modes produce unique spectroscopic signatures, many of which have been studied in labs here on Earth (Chown et al. 2024; Öberg et al. 2023; Jorgenson et al. 2020). Due to a particularly strong spectroscopic feature appearing at around 8 mm, the Spitzer Space Telescope has been instrumental in tracing out these PAH molecules in interstellar space. The Infrared Array Camera (IRAC) aboard the Spitzer telescope surveys the near- and mid-infrared spectrum with four imaging channels centered at 3.6, 4.5, 5.8, and 8.0 μm; the fourth channel is especially effective at detecting the presence of PAH molecules in space due to the bright emission band at 7.7 μm. (Ehrenfreund & Charnley 2000).

The Spitzer telescope also contains the Multiband Imaging Photometer for Spitzer (MIPS), which surveys the mid- to far-infrared part of the spectrum. Its three channels, centered at 24, 70, and 160 μm, are used to trace out relatively warm interstellar dust. Since the blackbody radiation from stars is virtually undetectable at these long wavelengths, the radiation in this range comes almost entirely from warm dust at temperatures of less than about 300 K. This warm dust has also been found in known regions of star formation and is thus another important tracer of active star formation.

By combining H-alpha, 8 μm, and 24 μm imagery, it is possible to respectively assess the ionized, molecular, and granular phases of the ISM in the context of recent star-forming activity in M33. We carried out this study by taking a detailed look at eight selected HII regions, for which Spitzer Infrared Spectrograph (IRS) spectral scans are available. We also made a more global comparison of the emitting phases by considering galactocentric profiles of surface brightness at each wavelength band.

Data Reduction

To perform our analysis, we used imaging data from the Spitzer Space Telescope’s IRAC and MIPS instruments, as well as H-alpha data from the Burrell Schmidt Telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory (KPNO). For the PAH and dust phases, we respectively utilized Channel 4 of the IRAC camera (peaked around 8.0 mm) and the 24 μm channel of the MIPS camera. The IRAC data was taken as part of the Spitzer Guaranteed Time Observing (GTO) program under P.I. Robert Gehrz and was processed using version 14.0.0 of the Spitzer Science Center basic calibrated data (BCD) pipeline, incorporating over 1500 frames into the final mosaic. The MIPS data was extracted using version 2.96 of the MIPS Enhancer software. The continuum-subtracted H-alpha mosaic was obtained with the 0.6-m Burrell-Schmidt camera at KPNO (Long et al. 2010) and was kindly provided by Frank Winkler. Image sizes of the final mosaics from each instrument ranged from 2400×3000 to almost 4000×4500 pixels. All further image processing was done using the PerlDL scripting language (https://pdl.perl.org/).

We first rebinned all images onto the same grid with matching pixel size of 1.5”/pixel (the original pixel size of the H-alpha image). We then corrected for a background gradient in the IRAC 8 mm image and subtracted a constant background level in the MIPS 24 μm and H-alpha images. In order to perform resolution matching among the images, we used a characteristic point-source function (PSF) for each individual instrument: for the 8 μm data, a PSF generated by M. Marengo; for the 24 μm image, a PSF obtained from the Spitzer Science Center (SSC) website; for the H-alpha image, a PSF generated manually by sampling many point-like objects within the image itself, centering them, summing them together, and taking the composite image as the PSF. As would be expected, the resolution of the MIPS image was the limiting factor in resolution matching.

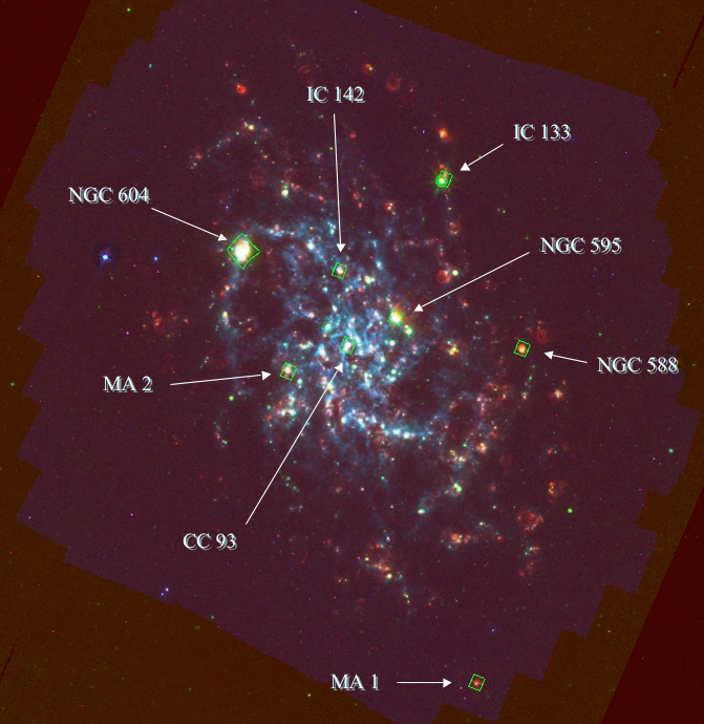

The composite RGB image can be seen in Figure 1, with 8 μm presented in blue, 24 μm in green, and H-alpha in red. Visual inspection of this composite image already reveals extensive H-alpha emission throughout the galaxy, with the 8 mm PAH and 24 μm dust emission falling off more rapidly with galactocentric distance.

Note in Figure 1 the distribution of the eight HII regions that are labeled in the diagram. For each of these regions we extracted a 150”x150” map capturing the central features of the H-alpha emission. To examine the relative distribution of the three components within these regions, we made flux-ratio maps comparing the 8 μm to 24 μm, 8 μm to H-alpha, and 24 μm to H-alpha emission for each region. Examples can be seen in Figures 2 to 9. We then plotted the radial distribution of each component normalized to that in the central core. Because the 24 μm emission tended to be more localized than the 8 μm and H-alpha emission, for most regions we defined the central core as the location in the HII region where the 24 μm was most sharply peaked (with the exception being some regions with relatively low 24 μm emission, in which case we used the approximate the center of the extended H-alpha component).

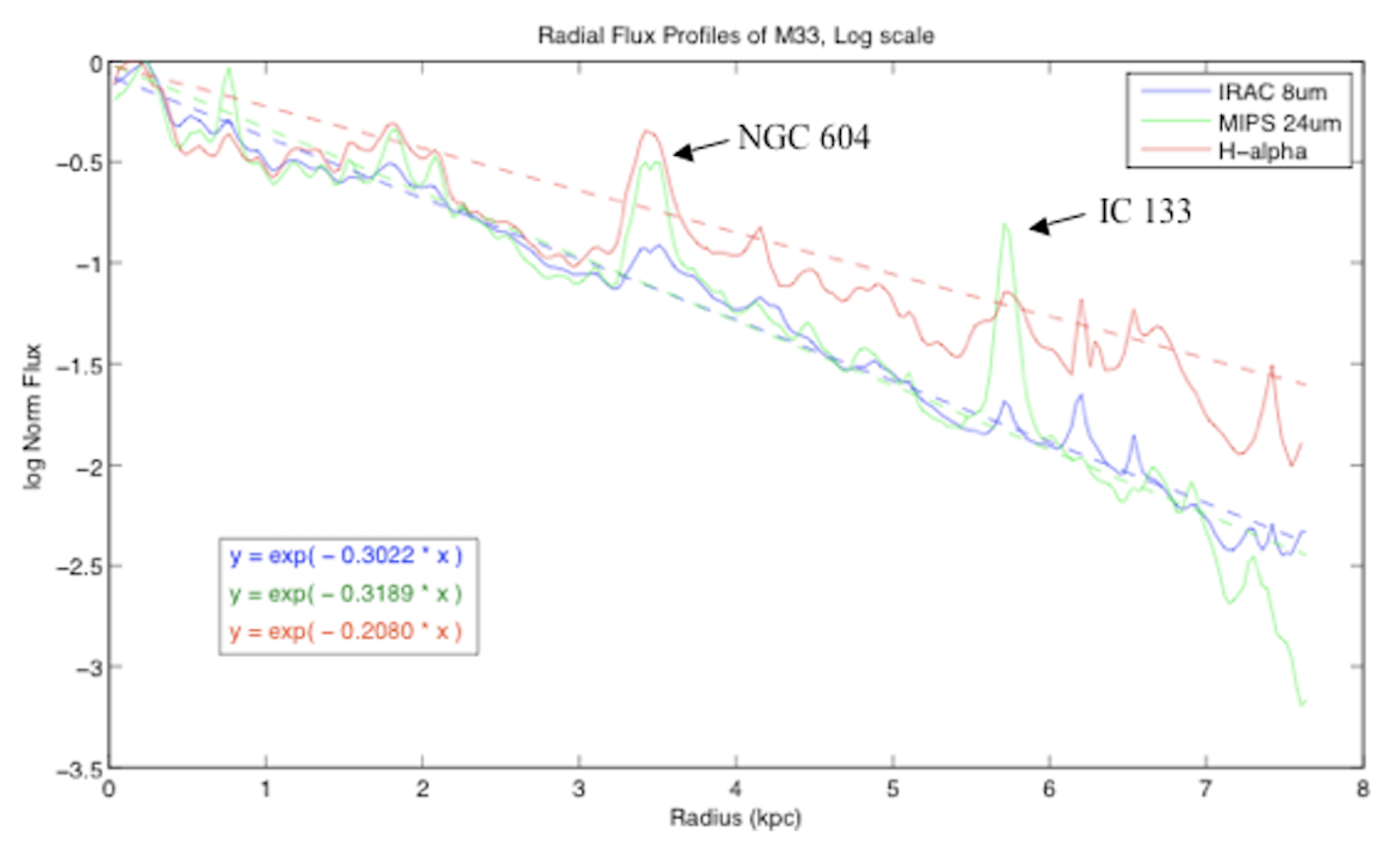

Finally, we plotted the overall radial distribution of each nebular component with respect to distance from the center of the galaxy. To do this we first corrected for the inclination and tilt of the galaxy, then plotted the average flux of each component as a function of galactocentric radius. We did this out to a rectified radius of 30’ (7.3 kpc), in increments of 7.5” (30.5 pc). The overall galactocentric distribution is shown in Figure 12, with each wavelength component normalized to one at the nucleus.

HII Regions

We analyzed eight prominent HII regions within M33: CC 93, IC 142, IC 133, NGC 588, NGC 595, MA 1, MA 2, and NGC 604. These HII regions manifest a significant range of metallicities, thereby enabling a study of possible variations in star-forming activity as related to metallicity. Spitzer IRS spectral scans have been made with preliminary results confirming the broadband results presented here (Waller et al., 2005a, 2005b, 2006).

We present analysis and imagery of each region below in a sequence that best highlights their similarities and differences. Each frame is 150’’ (610 pc) on a side, with north up and east to the left. Flux ratios are presented in greyscale, so that larger values are whiter.

Figure 1: M33, with 8.0 μm in blue, 24 μm in green, and H-alpha in red. The eight prominent HII regions which we studied in greater detail are enclosed in green squares and labeled.

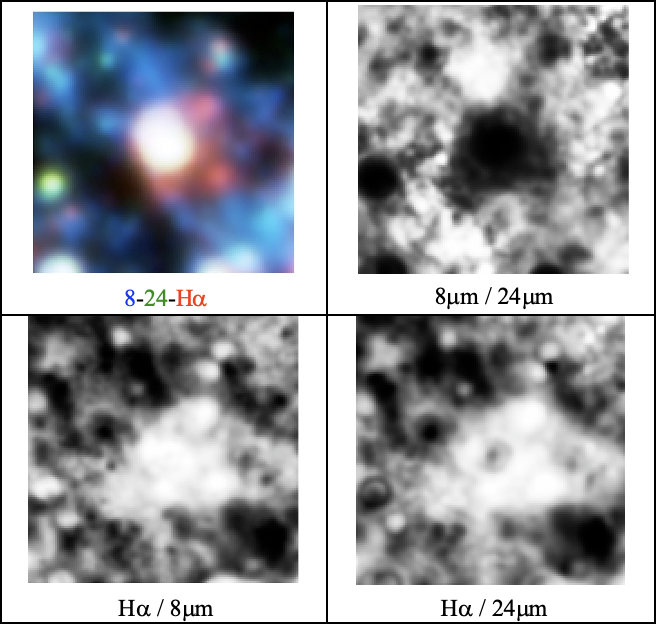

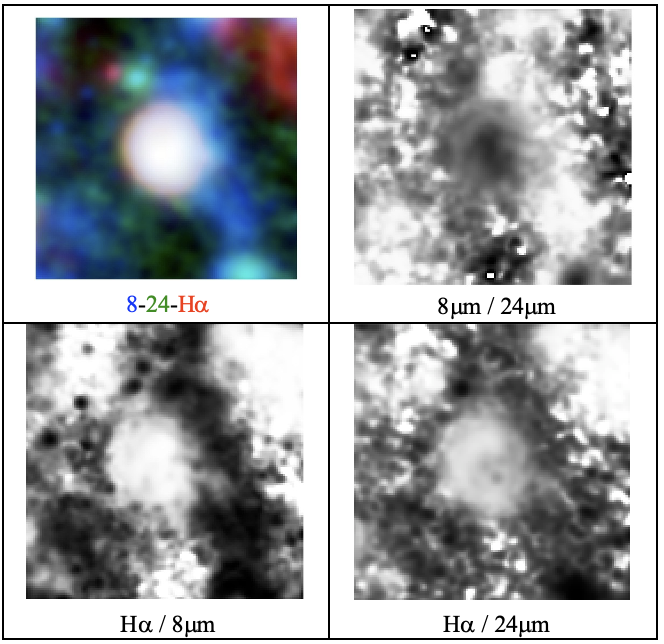

CC 93 is located near the galactic center. It contains a central feature rich in all three components. A series of localized pockets of warm dust, seen most prevalently in the 8μm / 24μm flux ratio image, suggest possible regions of star formation surrounding the central core.

Figure 2: CC93 color composite (upper-left) and flux-ratio images.

IC 142 is located directly north of the galactic center at the base of a spiral arm. It displays rich extended H- alpha emission, with a small localized region of warm dust (traced by the 24 μm emission). The PAHs (traced by the 8 μm emission) appears to be the most extended phase in this region.

Figure 3: IC 142 color composite (upper-left) and flux-ratio images.

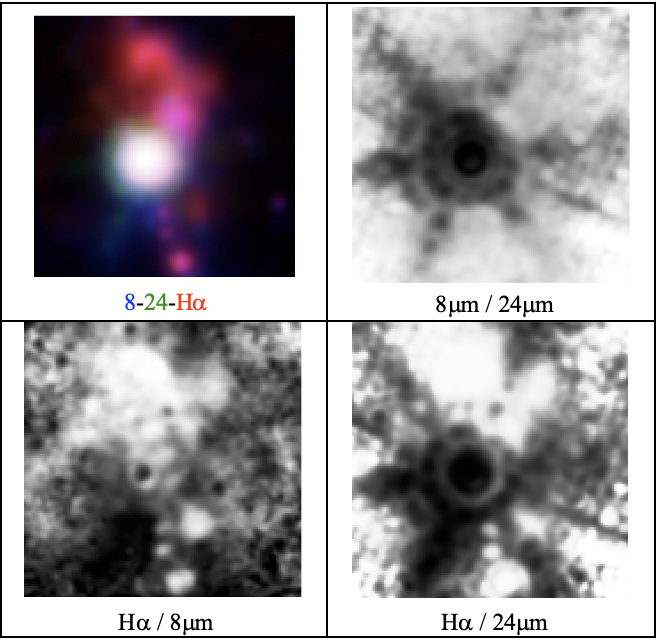

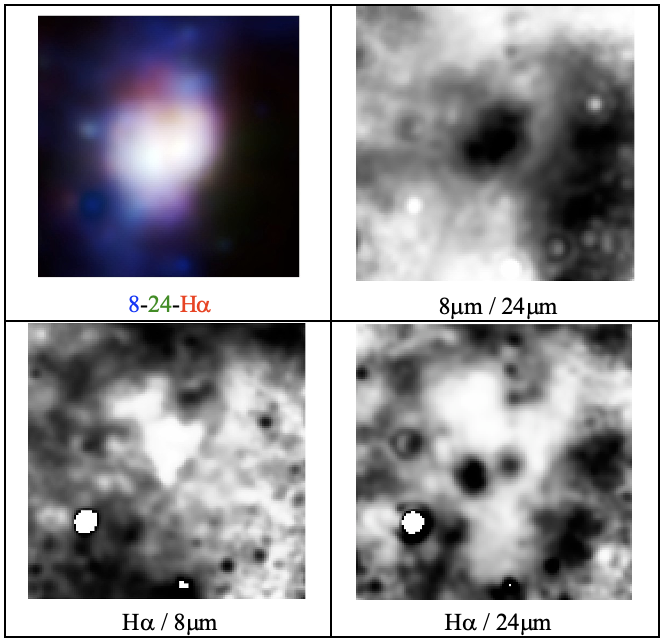

IC 133 features an unusually strong 24 μm emission core. This could indicate the presence of a dust-embedded centrally- condensed star formation region. There is also evidence for a water vapor maser in IC 133 (Argon et al. 2004), further corroborating the dense nebular circumstances and strong IR radiation field. Extended H-alpha emission is evident to the north and south of the core.

Figure 4: IC 133 color composite (upper-left) and flux-ratio images.

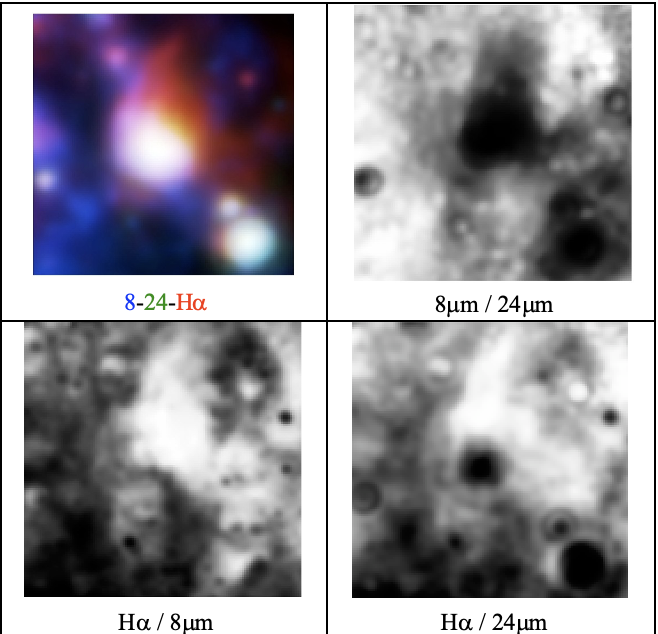

NGC 595 is located slightly north-west in the inner part of the galaxy. It is the second brightest HII region in M33. It provides yet another example of a localized 24μm emitting core contained within a more extended region of ionized gas and PAHs. Also note the two nearby pockets of concentrated 24 μm emission just south-west of the central core – this could be indicative of other deeply embedded star forming regions.

Figure 5: NGC 595 color composite (upper-left) and flux-ratio images.

NGC 588 is located on the far western edge of M33 near the tip of a large spiral arm. It is relatively weak in both the 8 μm and 24 μm components compared to the H-alpha emission, unlike the strong core- dominated PAH and dust emission of the inner HII regions. Beyond the HII region’s core, a ridge of enhanced 8 μm emission is evident.

Figure 6: NGC 588 color composite (upper-left) and flux-ratio images.

MA 1 can be found on the extreme southern tip of the galaxy. Like NGC 588, it is also quite deficient in 8 μm and 24 μm emission but has a strongly localized H-alpha emitting core. The relative lack of 8 and 24 μm emission for both MA 1 and NGC 588 could possibly be explained by their location in the far outer disk of the galaxy, where the metallicity is much less (~0.1 solar).

Figure 7: MA 1 color composite (upper-left) and flux-ratio images.

MA 2 is located slightly south-east of the galactic center. It is possibly another example of multiple star formation regions within a more extended cloud of ionized gas. Not only is there a strong presence of heated dust in the central core (seen most prominently in the 8μm / 24μm flux-ratio image), there are also other strongly localized pockets of 24μm emission nearby.

Figure 8: MA 2 color composite (upper-left) and flux-ratio images.

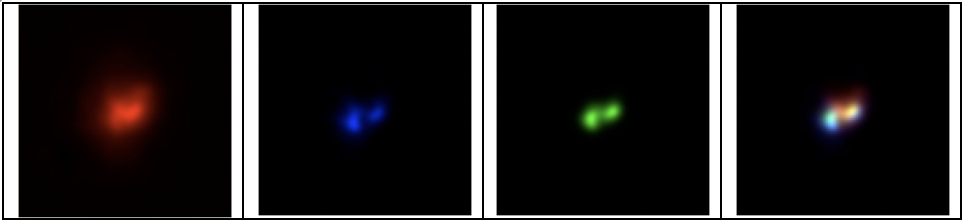

NGC 604 is the most powerful and arguably the most interesting HII region in M33. It extends over a region of approximately 1,500 light years (roughly 40 times larger than the Orion Nebula) and is buzzing with activity. Most notably, we discovered dual star forming cores in the center of this great cloud, seen best in 8 μm and 24 μm emission (see figure 10 below). The eastern (left) core shows very little ionized gas, indicating that it is deeply embedded.

Figure 9: NGC 604 color composite (upper-left) and flux-ratio images.

Figure 10: Examining the dual star forming cores of NGC 604. There appears to be very little H-alpha emission (red) in the eastern core, compared with the 8 μm (blue) and 24 μm (green) emission, which indicates a deeply embedded star formation region.

Angular Distribution of Components Inside HII Regions

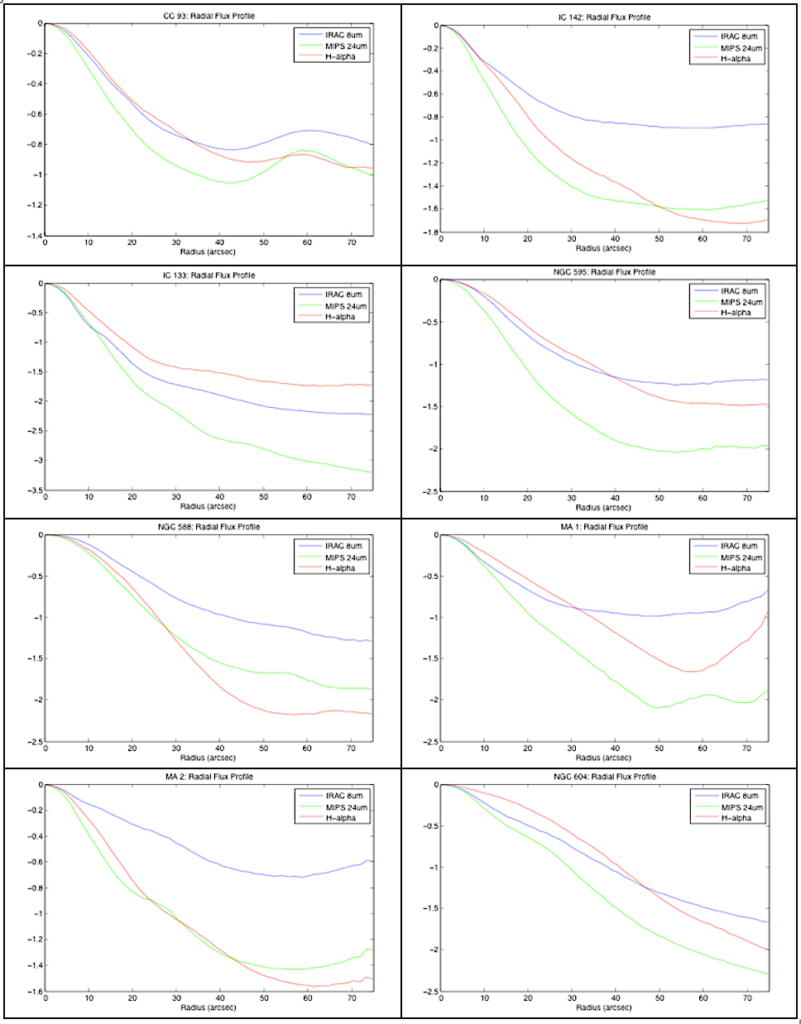

For each HII region, we analyzed the radial distribution of each component from the central core. These results are shown in Figure 11. In almost every case, the 24 μm emission was the most compact component, indicating that warm dust is the best tracer of clustered high-mass star formation. The 8 μm and H-alpha emission appear to be much more extended throughout the HII regions. The one region which deviated significantly from this trend was NGC 604, the supergiant HII region. The sheer size of this region could play a role in spreading out the radial profiles of emission in all three phases. The dual star-forming cores at the center, as described above, also could be contributing to the similar radial profiles.

What Figure 11 does not show are the actual radial distributions of fluxes within each HII region. These fluxes vary from high values at 8 μm and 24 μm relative to those at H-alpha for HII regions in the inner galaxy vs. ~10-times weaker 8 μm and 24 μm fluxes for HII regions in the outer galaxy. These photometric results are consistent with the HII region photometry obtained by Relaño & Kennicutt (2009), where the 8 μm/H-alpha and 24 μm/H-alpha flux ratios in NGC 588 are down relative to those in NGC 604 by factors of 12.9 and 7.4, respectively. Similarly, the same flux ratios are down in NGC 588 relative to NGC 595 by factors of 10.4 and 6.3, respectively.

Galactocentric Distribution

We also measured the galactocentric profile of surface brightness for each nebular component over the entire galaxy, after accounting for the inclination of the galaxy and taking annular averages. The resulting plot of normalized flux vs. galactocentric radius is shown in Figure 12. We fit the radial decline of each emitting component by a simple exponential; the fit parameters are shown in the plot. While the 8μm and 24 μm emission follow a steady decrease with galactocentric radius, the H-alpha emission has a shallower decline in the outer regions of the galaxy. In fact, a better fit can be achieved by applying a double-exponential decay to the H-alpha emission as opposed to a single-exponential. Similarly shallow radial profiles are evident at ultraviolet wavelengths, thus supporting the notion of extensive massive star formation in M33’s outer disk, where the molecular and dust emission is relatively weak (Marcum et al. 2021).

We can see this trend mirrored in our photometry of the outermost HII regions, MA 1 and NGC 588. Both are very weak in 24 μm emission, and to a lesser extent 8 μm emission, indicating that relatively low amounts of organic molecules and dust characterize the star-forming environments in the outer parts of the galaxy.

Figure 11: Radial profile of intensities for each HII region, shown as radius from central core (x-axis) vs. the logarithm of the normalized flux (y-axis). The radial extent of each plot is 75”, corresponding to about 300 pc. For all plots, 8 μm is represented by blue, 24 μm by green, and H-alpha by red.

Figure 12: Plot of the normalized flux (log scale) vs. galactocentric radius. The H-alpha (red) emission falls off much more slowly in the outer regions of the galaxy than either the 8 μm (blue) or 24 μm (green). This indicates a relatively low-PAH and low-dust environment for star formation in the outer galaxy.

Conclusions and Discussion

Our study of star formation in Messier 33 included eight HII regions: CC 93, IC 142, IC 133, NGC 588, NGC 595, MA 1, MA 2, and NGC 604. Using the IRAC 8.0 μm channel, the MIPS 24 μm band, and H-alpha data, we were able to analyze the relative abundance of PAHs, warm dust, and ionized gas in each region. In general, we found that the 8 μm and H-alpha emission tends to be more extended, while the 24 μm emitting dust is more highly localized and compact. This implies that warm dust may be the best tracer of star formation within HII regions.

Additionally, we measured the average intensity of each emitting interstellar phase as a function of galactocentric radius. We found a similar decline with radius for each phase in the inner parts of the galaxy, out to about 3.5 kpc. However, in the outer regions of the galaxy, the H-alpha emission follows a much shallower decline than the 8 μm and 24 μm emission. This is likely due to a physical decrease in the abundance of PAHs and warm dust in the outer regions of the galaxy, and thus a more dust-free environment for star formation than in the inner galaxy.

An alternative explanation for the shallower fall-off of H-alpha emission with increasing distance from the galaxy’s center focuses on the varying dust content and its interaction with the ionizing photons from the hot embedded stars. The excess dust in the galaxy’s interior could be competing against the gas for the ionizing photons, thus reducing the ionization rate and corresponding H-alpha emission there. This process could be responsible for flattening the H-alpha’s galactocentric emission profile relative to that of the 24 μm and 8 μm emission. Moreover, no amount of de-reddening of the H-alpha emission via comparison with other hydrogen recombination lines or with the thermal radio continuum will compensate for this shortfall of ionization, as the competition for ionizing photons occurs before the gas becomes ionized.

One way to discriminate between these two explanations is to consider and compare other tracers of the multi-phase ISM. Mappings of M33 in the 21-cm line of atomic hydrogen reveal essentially a flat galactocentric profile, while comparable mappings in the 2.6-mm line of carbon dioxide yield a profile that declines by a factor of 8 over 6 kpc in galactocentric radius (Utomo, Blitz, and Falgarone 2019). Once again, the metallicity-dependent CO emission appears to decline significantly with galactocentric radius, thus bolstering the case for actual declines in the PAH and dust abundances at large galactocentric radii.

Acknowledgements

We thank Robert Gehrz and the Spitzer/M33 Research Team for access to their infrared mosaics of M33. We also thank Frank Winkler for providing optical emission-line and red- continuum images of M33 obtained with the Burrell-Schmidt telescope. We are especially grateful to Massimo Marengo for the use of his resolution matching point spread function (PSF) and helpful advice overall. This work is based on observations made with the Spitzer Space Telescope, which is operated by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology under NASA contract 1407. W. H. W. acknowledges support through NASA/JPL under Spitzer GO program 3280. T. D. Weinbeck acknowledges support from NASA through a student fellowship from the Massachusetts Space Grant Consortium.

Tony Weinbeck is currently a PhD student at the University of Wyoming. Tony earned his Bachelor’s degree at MIT and his Master’s degree at Tufts University. He went on to teach astronomy at Normandale Community College in the Twin Cities while honing his skills in astrophotography. At U. Wyoming, he has been pursuing extragalactic research with the PHANGS team using data from the James Webb Space Telescope. (weinbeck@alum.mit.edu)

References

Argon, A. L., et al. (2004), “The IC 133 Water Vapor Maser in the Galaxy M33: A Geometric Distance,” Astrophysical Journal, vol. 615, p. 702.

Chown, R. et al. (2023), “Aromatic infrared bands in the Orion Bar,” Astronomy & Astrophysics, vol. 685, p. A75.

Corbelli, E. & Salucci, P. (2000), “The Extended Rotation Curve and the Dark Matter Halo of M33,” Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, vol. 311, p. 441.

Ehrenfreund, P., & Charnley, S. B. (2000), “Organic Molecules in the Interstellar Medium, Comets, and Meteorites: A Voyage from Dark Clouds to the Early Earth,” Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, vol. 38, p. 427.

Freedman, W. L., et al. (2001), “Final Results from the Hubble Space Telescope Key Project to Measure the Hubble Constant,” Astrophysical Journal, vol. 553, p. 47.

Jorgenson J. K., Belloche A. Garrod R. T. (2020), “Astrochemistry During the Formation of Stars,” Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, vol. 58, p. 727.

Koning, A. H. (2016), “Metallicity Map of M33,” Master’s Thesis, University of Alberta, https://era.library.ualberta.ca/items/43f96ed2-ce57-4a8f-906e-820450a9512f

Long. K. S., et al. (2010), “The Chandra ACIS Survey of M33: X-ray, Optical, and Radio Properties of the Supernova Remnants,” Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, vol. 187(2), p. 45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0067-0049/187/2/495

Marcum, P., et al. (2021), “AnUltraviolet/OpticalAtlasofBrightGalaxies,” Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, vol. 132, p. 129.

Öberg K. I., Fachini S, & Anderson D (2023), “Protoplanetary Disk Chemistry,” Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, vol. 61, pp.287-328.

Relaño, M. & Kennicutt, R. C. Jr. (2009), “Star Formation in Luminous HII Regions in M33,” Astrophysical Journal, vol. 699, p. 1125.

Rosolowsky, E., & Simon, J. D. (2008), “The M33 Metallicity Project: Resolving the Abundance Gradient Discrepancies in M33,” Astrophysical Journal, vol. 675, p. 1213.

Shields, G. (1990), “Extragalactic HII Regions,” Annual Review of Astronomy and

Astrophysics, vol. 28, p. 525.

Utomo, D., Blitz, L., & Falgarone E. (2019), “The Origin of Interstellar Turbulence in M33,” Astrophysical Journal, vol. 871, p. 17.

Tielens, A. G. G. M. (2005), The Physics and Chemistry of the Interstellar Medium, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

Waller, W. H., Murphy, E. J., Gehrz, R. D., Polomski, E., Woodward, C. E.,

Fazio, G. G., Rieke, G. H., and the Spitzer/M33 Research Team (2005a), “Circumstantial Starbirth in Starbursts: Systematic Variations in the Stellar and Nebular Content of Giant HII Regions in the Local Group Galaxy M33,” Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society, vol. 37, p. 1423

Waller, W. H., Murphy, E. J., Gehrz, R. D., and the Spitzer/M33 Research Team (2005b), “Multiwavelength Diagnostics of Starbirth in Starbursts,”

Waller, W. H., Murphy, E. J., Gehrz, R. D., Polomski, E., Woodward, C. E., and the Spitzer/M33Research Team (2006), “Spitzer Spectroscopy of Giant HII Regions in M33 – Evidence for Systematic Variations in the PAH and Dust Content,” Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society, vol. 38, p. 102.