William H. Waller

What a difference a wintry month can make. On January 13-16, the American Astronomical Society (AAS) held its bi-annual meeting in Baltimore, MD. Donald Trump had been (re)elected President but had yet to be inaugurated and enter office on January 20. The overall mood at the AAS meeting was a bit nervous, as people wondered what priorities the new administration would take on first. But overall, the focus at the meeting could remain on the science of astronomy, with many presentations on the latest research findings and educational developments shared, and with many opportunities for professional networking.

Fast forward to the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) that occurred in Boston, MA on February 14-16. The Trump administration was in full swing, with many of the cabinet appointments filled and an agenda that was dizzying in its reach and impact. The proverbial feces had hit the fan. Already, many folks within the scientific community had been targeted for reductions in force. These included scientists at the National Institutes of Health, Environmental Protection Agency, Department of Energy, NSF, NOAA, and NASA. Entire departments associated with diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) had been scrubbed, while most energy projects designed to wean us off fossil fuels were scrapped. In a reprise from the 2016-2020 Trump administration, any mention of human-caused climate change was stifled. A more detailed account of the rattled mood at the AAAS meeting can be found at https://www.statnews.com/2025/02/17/aaas-meeting-science-research-trump/

Given these circumstances, many speakers recognized the grim realities affecting the American scientific enterprise yet managed to soldier on with righteous purpose. And for good reason, as many sciences – including astronomy – were well represented at the meeting. In these dispatches from the cosmos, I will describe a few astronomical highlights that I gleaned from both the AAS and AAAS meetings.

New Sources of Cosmic Dust:

Just like the dust that stubbornly besmirches your computer monitor, bookcase, and ancestral credenza, cosmic dust is now recognized to have a multiplicity of origins. For decades, astronomers thought that aging red giant stars produced most of the dust responsible for obscuring and reddening our views of nebulae and more distant stars … and for making rocky planets such as Earth. In the outer atmospheres of these distended stars, gases of silicon, oxygen, and carbon could cool, coalesce, and solidify into microscopic grains of silicates and graphites. Once the star enters its unstable asymptotic giant branch (AGB) phase, it will expel these grains of dust into the ambient interstellar medium. Recently, astronomers have found another major source of dust in the supernova explosions that result from the sudden collapse of a massive star’s dormant core. These so-called Type II supernovae eject much of the dying star’s atmosphere, shocking the gases in the process, and so forging new grains of dust.

Fifteen years ago, the infrared Spitzer Space Telescope found that supernovae of type IIn were especially dusty. These supernovae explode into pre-existing shells of circumstellar material, thus driving the collisional creation of dust. One particular supernova, SN 2005ip, was observed in 2008 by Spitzer to have produced a strong spectroscopic signal from hot carbon dust. In 2021, follow-up observations by the James Webb Space Telescope revealed compelling evidence for silicate dust having formed from the cooling supernova (see Fig. 1). In her presentation on these results, Melissa Shahbandeh (STScI) noted that supernova-driven dust formation helps to explain the emergence of dusty galaxies in the very early universe – when the rate of massive star formation and explosive death was much greater than it is today.

Fig. 1: Screenshot from Melissa Shahbandeh’s presentation on “Supernovae as Key Dust Producers” at the January 2025 meeting of the AAS. (Credits: M. Shahbandeh et al. 2025, https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.09142)

Thanks to the Webb telescope, astronomers have also been able to track the creation and expulsion of dust in the form of concentric shells from the hot massive binary star system WR 140. These so-called Wolf-Rayet stars are especially hot and windy. In the case of WR 140, there are two of these stars in elongated orbits that take them very close to one another every 8 years. When the stars get closest to one another, their intense winds collide and so produce a shell of dust that flies outward at 2,700 km/s – almost 1 percent the speed of light. Images from the JWST show the warm shells of dust in exquisite detail (see Fig. 2). In her presentation, Emma Lieb (Denver University) highlighted the importance of these sorts of stellar phenomena in generating the cosmic dust that is so essential to forming rocky planets and ourselves.

Fig. 2: JWST mid-infrared images of the Wolf-Rayet binary star system WR 140 over two epochs separated by 14 months have revealed 17 concentric shells of newly forged dust that are expanding outward at high speed. The right panel shows how much the shells have moved over 14 months. (Credits: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI)

Our Gassy Galaxy:

Our Milky Way galaxy hosts more than a billion suns worth of cold gas in the form of giant molecular clouds. Why these clouds are not rapidly collapsing under their own weight in an orgy of rampant star formation remains a cloying question to many galactic astronomers. One possible explanation is that energetic feedback from the star-forming activity is pressurizing the molecular clouds against collapsing. Searing ultraviolet radiation, intense winds, and – ultimately – powerful supernova explosions from massive stars can all provide the necessary feedback. To investigate these phenomena throughout the Milky Way galaxy, the Sloan Digital Sky Survey Local Volume Mapper team has developed a suite of four robotic telescopes that feed their light into four separate spectroscopes via optical fibers (see Fig. 3). The resulting output of 36,000 spectra per exposure yield maps of the spectral-line emission coming from clouds of ionized gas. Once stitched together, the 55 million spectra will yield a complete survey of ionized gas species across the Milky Way. Spatial variations in the respective strengths of line emission from ionized hydrogen, oxygen, sulfur, and nitrogen can be diagnosed in terms of the stellar powering from UV emission, winds, and explosions.

This survey builds on the prior WHAM survey of ionized hydrogen in the Milky Way that made use of a type of narrowband filter capable of being tuned to a particular wavelength emitted by ionized hydrogen. In the new survey, entire spectra are generated thus yielding maps of many different ionized species.

In his talk, Dannesh Krishnarao (Colorado College) emphasized the team’s work toward increasing the participation of underserved communities by providing access to the scientific data, insights, and mentoring. The project is in its initial stages with a whole lot more to go.

Fig. 3a: Rendering of the four telescopes and spectrographs that make up the Local Volume Mapper, a novel robotic observatory that will survey the spectral-line emission coming from ionized clouds across the entire Milky Way. (Credits: FAST program, Sloan Foundation, NSF)

Fig. 3b: Maps of the spectral-line emission from the Rosette Nebula. Emission-line maps of ionized hydrogen, helium, oxygen, sulfur, and nitrogen are represented in this mandala. (Credits: FAST program, Sloan Foundation, NSF)

The Largest HST Image – Ever!

Some of you might own a sophisticated SLR camera with an electronic array detector that contains up to 60 million pixels. Well, that’s chicken feed compared to what astronomers have managed with imagers on the Hubble Space Telescope. Focusing on the Andromeda Galaxy (M31), they have created a multi-color mosaic that contains 2.5 billion pixels – the largest HST image ever! Over a period of ten years involving two major programs that together required 1,000 orbits of observing time, they took 14,394 images covering 609 positions in the galaxy that were then stitched together to make the photomosaic (see Fig. 4a).

Fig. 3a: Photomosaic of the Andromeda Galaxy (M31) with closeups of young star clusters, the meddlesome dwarf galaxy M32, and obscuring lanes of dust in silhouette against a background of myriad stars. The large outline of a half circle to the upper right indicates the size of the Moon for comparison. The photomosaic shows differing colors that indicate differing stellar populations — with the mellow yellow starlight in the central bulge denoting evolved giant stars, and with the bluish starlight in the surrounding disk consisting of young hot stars of high mass and short lifetimes. (Credits: NASA, ESA, Benjamin F. Williams [U. Washington], Zhuo Chen [U. Washington], L. Clifton Johnson [Northwestern U.]; Image Processing: Joseph DePasquale [STScI])

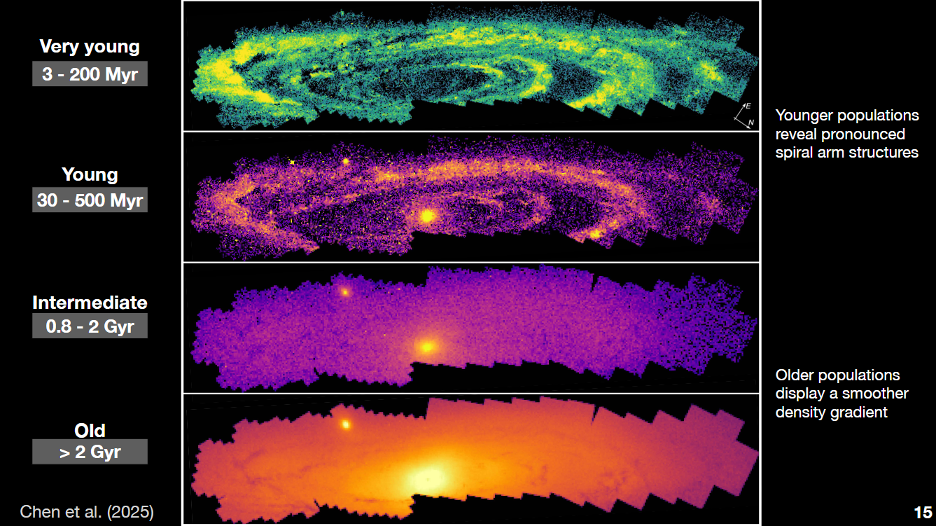

All told, the photomosaic resolves 200 million stars in the galaxy. This is roughly 1/1,000 the total estimated number of stars inhabiting M31, but it’s enough to parse the stars into separate populations according to their colors, luminosities, and corresponding ages (see Fig. 4b). The older stars appear smoothly distributed from the central bulge and into the disk. These stars have been around the block many times and so have roamed from their birthplaces to create a smear of habitation. By contrast, the youngest stars still trace their birthplaces within the spiral arms of the disk. The spiral arms appear more like distorted rings – a testament to the gravitational provocations induced by the captured galaxies M32 and M110 (NGC 205). With its large central bulge and wonky disk, M31 appears to be transitioning from being a spiral system to becoming an elliptical galaxy.

Fig. 4.5b: Spatial distributions of stars in M31 according to their ages, as presented by Zhuo Chen (University of Washington) at the AAS meeting. The older stars are smoothly distributed, while the younger stars are confined to ring-like spiral arms. (Credit: Screenshot from Zhuo Chen’s presentation)

Half of the Hubble Tension Appears Settled:

At the February AAAS meeting in Boston, Nobel prize winner Adam Weiss provided an update on the quest to resolve the so-called Hubble Tension. This vexing issue in cosmology comes from the stubborn disparity in the expansion rate of the universe as measured from data in the nearby current-epoch universe vs. data from the distant primordial universe. The expansion rate is known as the Hubble constant, or Ho. Measurements of distances to nearby galaxies, when compared with measurements of their redshifts (interpreted as recession velocities), yield an expansion rate of Ho = 73.04 km/s per megaparsec of distance. Contrast this value of the Hubble constant with that predicted from the spacing of irregularities in the Cosmic Microwave Background – the echo of the hot Big Bang, when ordinary matter was just beginning to cool from an ionized plasma state to a neutral atomic state. These irregularities are thought to be the imprints of sonic disturbances in the primordial plasma, some 380,000 years after the Big Bang. Their spacing of about a degree on the sky constrain models of the cosmic expansion to yield a current-epoch expansion rate of 67.5 km/s per megaparsec – hence the disparity and the so-called Hubble Tension.

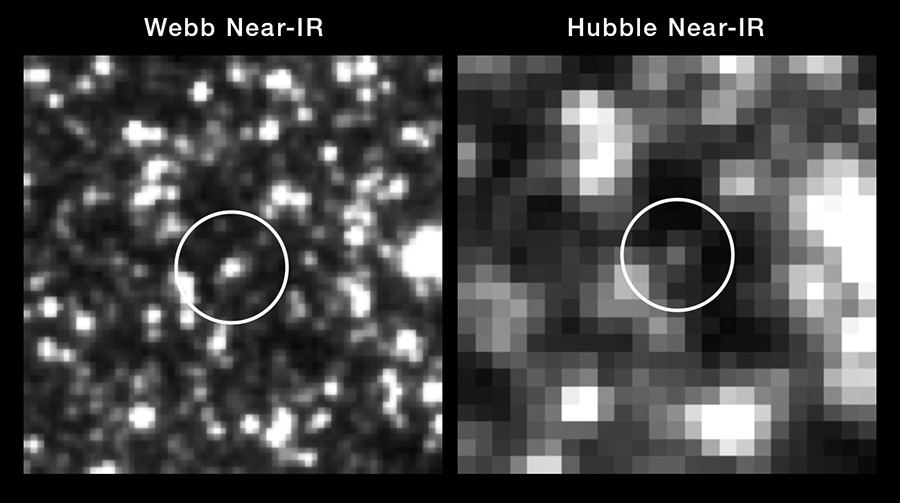

In his presentation, Weiss gave a compelling case for the nearby current-epoch universe having a well-constrained value of the Hubble constant. This value has benefited from recent efforts to reduce uncertainties in the galactic distances from new observations of Cepheid variable stars with the James Webb Space Telescope. The JWST operates in the infrared with fantastic acuity, allowing for images of these standard candle stars to stand out sharply, with crowding reduced by a factor of two (see Fig. 5). The galaxies hosting these Cepheids also have hosted supernovae of Type Ia, thereby enabling a calibration of the relationship between a supernova’s brightness and its distance – a key relation in the cosmological distance ladder. The resulting value of Ho = 73.04 ± 1.04 km/s/Mpc now differs from the CMB-based value of 67.5 ± 0.5 km/s/Mpc by more than 6-sigma. The Hubble Tension is real, and it probably has something to do with some unknown physics modifying the cosmic expansion. Possible candidates include variations in the vacuum energy in the popular cold dark matter model, or another kind of dynamical dark energy holding forth in the early universe, or even modifications to Einstein’s theory of general relativity. Wow!

Fig. 5: Comparison of images taken by the Webb telescope’s near-infrared camera vs. the Hubble Space Telescope’s equivalent. The circular outline encloses a Cepheid variable star located in a galaxy that also hosted a Type Ia supernova – two critical rungs in the so-called cosmological distance ladder. The degree of crowding is clearly less in the Webb image thus enabling a more precise measurement of the star’s brightness. (Credits: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Adam G. Riess [JHU, STScI])

Too Many Galaxies in the Early Universe?

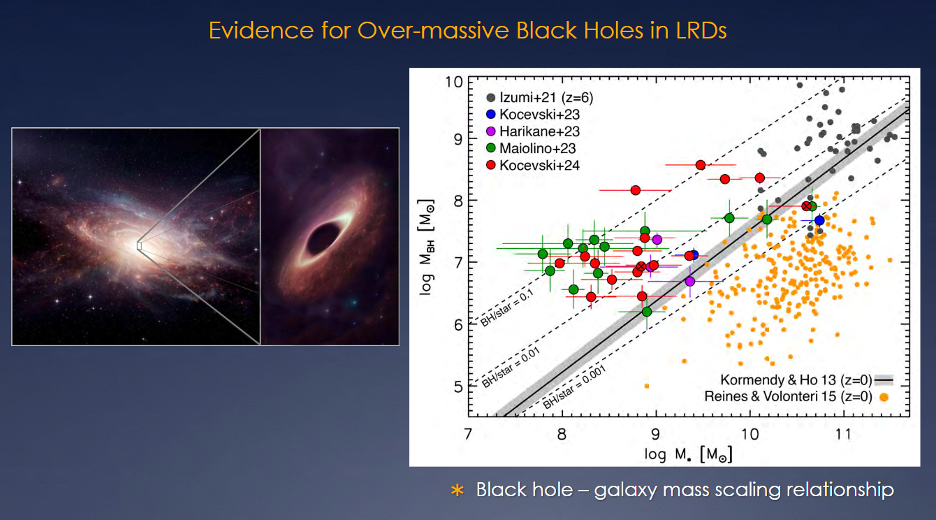

At both the AAS and AAAS meetings, astronomers publicly puzzled over the surprisingly large number of galaxies that the Webb telescope has found at high redshifts and correspondingly early epochs of the universe. These “little red dots” at redshifts of z = 3-8 and lookback times of 11.5-12.5 Gyr defy expectations based on models of galaxy formation in the primordial cosmos. In his AAS presentation, Dale Kocevski (Colby College) described spectra of these objects as showing ultraviolet excesses and broad emission lines which indicate active galactic nuclei (AGN) operating in their centers. These strange little beasts outnumber quasars by factors of a hundred and x-ray emitting AGN by factors of ten at similar redshifts. Moreover, the inferred masses of the central black holes are anomalously high compared to the masses of stars in these galaxies (see Fig. 6). It’s as if we might be witnessing an evolutionary mechanism, whereby black holes emerged first from the cooling chaos that followed the Big Bang – serving as “seeds” for the future growth of larger galaxies.

Fig. 6: Screenshot from Dale Kocevski’s AAS presentation on Little Red Dots (LRDs), showing depictions of a primordial galaxy, its central black hole, and the relation between the black hole’s mass and the host galaxy’s stellar mass. Typical galaxies in the local universe have black hole masses that are 0.001 the stellar masses in their hosting galaxies (shown as a grey band). By contrast, the LRDs have black hole masses that are 0.1 the stellar masses – thus outweighing the BH/Star mass ratio in current-epoch galaxies by a factor of 100. (Credit: https://webbtelescope.org/contents/news-releases/2025/news-2025-101#section-id-2)

At the AAAS meeting, Julian Muñoz (University of Texas at Austin) and his team extended JWST’s reach to redshifts greater than 9.5 and corresponding epochs less than 500 Myr after the Big Bang. Once again, he and his team found 100 times “more of everything” at cosmic dawn. Several of these red motes were found to be surprisingly massive – the equivalent of a hundred billion suns. Such an abundance of massive galaxies so early on challenge the notion of hierarchical galaxy growth, whereby galaxies bulk up via the slow process of merging and melding. Or are we misinterpreting the red light as coming from lots of low-mass stars? Instead, JWST could be detecting the light from scads of starbursting systems, thus biasing the rate of detections and so explaining the seeming overabundance. If so, the LRDs could be considerably less massive as well, thereby negating the need for some unusually rapid formation process.

Governance in Space:

In these most “interesting times,” astronomers on the ground must contend with light pollution from poor lighting practices that are exacerbated by the proliferation of unshielded and unfiltered LED lamps. Our skies are now riddled with constellations of satellites in low Earth orbit that reflect sunlight back to our detectors – essentially photobombing whatever astronomical images we endeavor to make. Literally looming above the horizon are other potential light polluters that include solar power generators as well as advertising platforms in low Earth orbit (see Fig. 7).

Fig. 7: Rendering of an advertising platform in low Earth orbit that is being proposed by a Russian advertising firm. (Credits: NBC and StartRocket)

On the surface of the Moon, international conflicts may soon arise as countries and companies vie for optimal real estate to carry out their various operations. The lunar south pole appears especially popular, as the rims of craters there enjoy continuous sunlight for solar powering while the floors of these same craters experience continuous darkness – thus preserving any valuable water in these locales. The far side of the Moon is radio quiet and so has special appeal to radio astronomers wishing to sense faint signals from the early universe without interference. Alas, multiple spacecraft in lunar orbit likely would introduce these sorts of meddlesome transmissions. Meanwhile, the pervasive lunar dust knows no borders, and so any disruptive operations on the surface will launch these tiny grains hither and thither, well beyond their sources. What’s a Moon-based astronomer to do?

At the AAS meeting, John Barentine (Dark Sky Consulting) brought us up to speed on the AAS’s Committee for the Protection of Astronomy and the Space Environment (COMPASSE). Active since 1988, COMPASSE currently tackles the issues of light pollution, radio frequency interference, space environment (satellite debris), and satellite constellations. Their activities and ways to get involved can be accessed at https://compasse.aas.org/.

At the AAAS meeting, I had the good fortune to be part of a “trending topics” luncheon for press that included a table focusing on space governance. Hosted by Jennifer Wiseman (NASA/GSFC) and Christopher Johnson (Secure World Foundation), the discussions covered historic agreements that go back to the United Nation’s Outer Space Treaty (1967), the Moon Treaty (1979), and more recently The Artemis Accords (2020). All these agreements prohibit “appropriations” of territory by any country, while encouraging peaceful cooperation among nations in their space activities. Chris Johnson highlighted the differences between “soft law” which involves the development of behavioral norms and “hard law” which involves enforcements of security issues. In 2022, the UN convened the Open-Ended Working Group (OEWG) on reducing space threats. This WG affirmed the need to avoid an arms race in space while putting forward better guidelines for responsible behavior. To secure the future of astronomy and other peaceful uses of space, they have their work cut out for them!